Dante's Florence

Dante's Florence

Of the greatest importance for the understanding of the "Divine Comedy" is a knowledge of the political doctrines and of the public life of Dante. Tuscany at that time was in a wild and stormy condition. It shared in the terrible disorders of the struggle between the Guelphs and Ghibellines (the former supporting the pope, the latter the emperor). It likewise had private quarrels of its own. The old feudal nobility had been repressed by the rise of the cities, into which the nobles themselves had migrated, and where they kept up an incessant series of quarrels among themselves or with the free citizens. Yet, in spite of this constant state of warfare, the cities of Tuscany increased in power and prosperity, especially Florence. We need only remember that at the time Dante entered public life (1300) an extraordinary activity manifested itself in all branches of public works; new streets, squares, and bridges were laid out and built; the foundations of the cathedral had been laid, and Santa Croce and the Palazzo Vecchio had been begun.

Portrait of Dante traditionally attributed to Giotto (or of the Giotto school).

Fresco in the Palazzo del Bargello, Chapel of the Magdalene, in Florence.

Such extensive works of public improvement presuppose a high degree of prosperity and culture. The political condition of Florence itself at this time was something as follows: In 1265 (to go back a few years in order to get the proper perspective), Charles of Anjou, brother of the king of France, had been called by Pope Urban IV. to Italy to aid him in his war against the house of Swabia; and through him the mighty imperial family of the Hohenstaufens, which had counted among its members Frederick Barbarossa and Frederick II., was destroyed. Manfred, the natural son of Frederick II., was killed at the battle of Beneventum (1266), and his nephew, the sixteen-year-old Conradin, the last member of the family, was betrayed into the hands of Charles after the battle of Tagliacozza and brutally beheaded in the public square of Naples (1268). It was through Charles of Anjou that the Ghibellines, who, having been banished from Flor- ence in 1258, had returned after the battle of Montaperti in 1260, were once more driven from the city, and that the Guelphs, that is, the supporters of the pope, were restored to power.

The government was subject to frequent changes, becoming, however, more and more democratic in character. The decree of Gian della Bella had declared all nobles ineligible to public office, and had granted the right to govern to those only who be- longed to a guild or who exercised a profession. It was undoubtedly to render himself eligible to office that Dante joined the guild of physicians. In 1300 he was elected one of the six priors who ruled the city for a period of two months only. From this brief term of office Dante himself dates all his later misfortunes.

At this time, in addition to the two great parties of Guelphs and Ghibellines, which existed in Florence as in the rest of Italy, there were in the city two minor parties, which at first had nothing to do with papal or imperial politics. These parties, known as Whites and Blacks, came from Pistoia, over which Florence exercised a sort of protectorate. The rulers of the latter city tried to smooth out the quarrels of the above local factions of Pis- toia, by taking the chiefs of both parties to themselves; but the quarrels continued in Florence, and soon the whole city was drawn into the contest, the Blacks being led by Corso Donati, and the Whites by the family of the Cerchi.

Altri articoli

The stone of the outrage

From 1282 priors were representatives of the seven Major guilds: they fighted against the old aristocratic families revenging an active role of trade in Florence.

What is done is done

This killing was the beginning of the civil florentine war between the aristocratic families factions of the city: Guelphs against ghibellines.

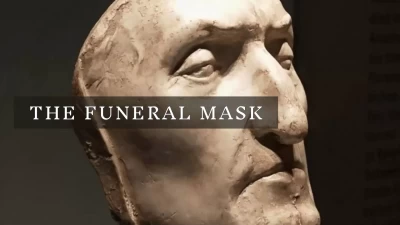

The funeral mask

The Dante funeral mask, once thought real, is now believed a lost sculptural portrait. Donated to Florence in 1911, found in Ravenna in 1830.

Florence and its illustrious Tuscan Men

These men are all watching the river Arno because they are defending Florence from the enemies!